{Audio pending}

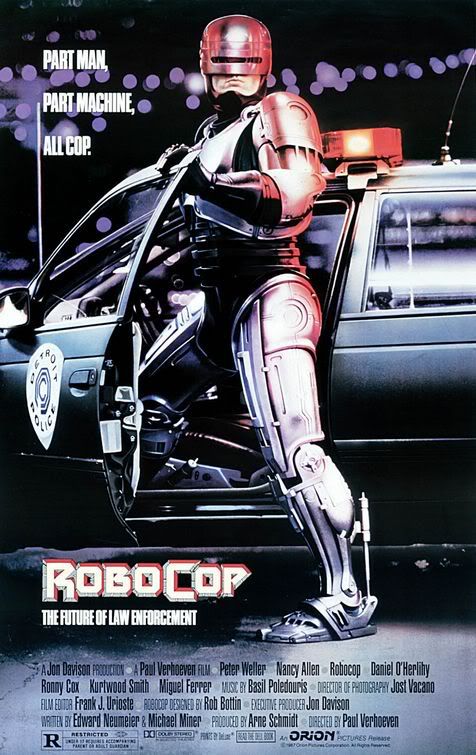

Capitalism is, in its current form, a very Darwinian way of life. Only the wealthy survive, and if you want to make it you need to cleave yourself to someone with pockets much deeper than yours in exchange for the means to keep on living. Lately the cleaving has been to large corporations instead of individuals. This is why you’ll see public sports arenas bearing the names of dispassionate banks and energy companies instead of the luminaries of the sport. This is called privatization, and it’s the basis for Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop.

Oh, and there’s a robot. Who’s a cop.

In a near-future vision born of the 80s and bearing a sharp, cynical edge, the police of Detroit have become owned and operated by Omni Consumer Products, a military subcontractor looking to bulldoze a crime-ridden part of the city to build an ultra-modern business district. When the old guard’s robotic answer goes awry during a demonstration, a young turk puts forth his own idea, involving the use of ‘some poor schmuck’. That schmuck is Murphy, a hard-working well-meaning cop transfered into the most violent precinct in the city just in time to killed in the line of duty. OCP scrapes him off of the operating room table, drops him into a robotic body and wires him with primary directives: Serve the public trust, protect the innocent, uphold the law. This is RoboCop, their hottest product ever, but inside the titanium and kevlar, does Murphy still exist?

RoboCop’s one of those movies I grew up with. When I first saw it, I was too young to understand a lot of the underlying themes of the work, but I understood the basics of the plot in and of themselves, and hey, badass robots! Seeing it again, I can appreciate it more on levels beyond mere spectacle and distraction. In fact, watching RoboCop as an adult, it’s hard to shake the notion that Verhoeven might as well be saying “This is what happens when people with money run everything” in big, bright letters.

Your move, creep.

That said, this is a Verhoeven entry much more in line with Starship Troopers than Black Book. Even more so than the theme of military pseudo-fascism, privatization is something that has remained a pertinent and very real possibility in our modern day and age. There are some of the classic Verhoeven tounge-in-cheek touches, like the stock tickers above the urinals in the OCP executive longue and the 8.2 MPG automobile called the 6000 SUX being hailed as “an American tradition”. These moments of levity not only serve as bridges between the visceral violence but also drive home the point our director is making.

Which isn’t to say that RoboCop is all cerebral anti-privatization rhetoric. There’s plenty of action to be had. From the gunfight in the coke factory to the showdown with ED-209, you’re certainly not going to be bored. It’s hard to shake the notion that the film’s age is starting to show in places, and some of the deeply-seated nuclear fears of the age seem a touch laughable, but the film has the good sense to laugh right along with us. However, it’s also hard to shake the feeling that some of the trends we see in the film – the beleagured, underfunded civil servants, the thriving corporations with rhetoric and iconography disturbingly close to a certain regime from the 1940s, the apathy of the public, the sensationalist news media – came to life all too vividly.

Say hello to Dick’s little friend.

On top of everything else, Peter Weller does a fine job in the lead role. As Murphy, he’s a nice guy in a bad town, wanting to do the right thing and impress his son while not being a very good shot and making a couple mistakes that lead to his demise. As RoboCop, it’s clear OCP has done all it can to strip him of his humanity, giving him an improved form and more accurate function while watering down all that made him who he was. The struggle he undertakes to regain what he lost, even in some small sense, inhabits this movie with some real heart that, while a touch melodramatic at times, nonetheless makes for a perfect final element to round out a great film.

I was afraid that the years had been unkind to RoboCop. While I did laugh at some of the stop-motion that chilled my blood as a child, I noticed a lot more now that I’ve grown. And everything I noticed just makes the movie better. If you’ve never seen RoboCop, be it because you were too young or you wished to avoid Verhoeven’s signature ultra-violence, do yourself a favor and queue it up on Netflix. Be it blazing action, darkly comedic satire or an intereting twist on a Frankensteinian character, there’s appeal for most within its runtime. It’s well worth your time.

Josh Loomis can’t always make it to the local megaplex, and thus must turn to alternative forms of cinematic entertainment. There might not be overpriced soda pop & over-buttered popcorn, and it’s unclear if this week’s film came in the mail or was delivered via the dark & mysterious tubes of the Internet. Only one thing is certain… IT CAME FROM NETFLIX.