I’m on my way to Boston for PAX East this morning. While I make my way through several states on what are certain to be lovely roads, have a look at my thoughts on the lines between video game developers and video game players, and what might happen if they get blurred.

I feel we are rapidly approaching what I’ve chosen to dub “the Video Game Singularity”. It’s the point at which the lines between developers and players of video games blurs to the degree that the storytelling experience these games convey is one truly shared between both camps. We’re on our way with RPGs with user mod tools like Skyrim, massively multiplayer experiences and yes, Choose-Your-Own-Adventure tales like the Mass Effect trilogy. Now, things like marketing departments, stratospheric fanatical expectations, and the limitations of current technology will hinder this advent, but it’s sooner than we think.

The Internet’s instant communication and dissemination of information is accelerating the process as we, as gamers, find and refine our voices. While we’ll never be able to excise every single idiot or douchebag from the community, we can minimize their impact while maximizing what matters: our investment in our entertainment. We are patrons, and video games are the art for which we pay.

Games are unquestionably art. Moreover, they a new form of art all their own, with their own traditions, their own classical periods, their own auteurs, their own mavericks. So I pose the question: why do we judge them as works of art extant in other forms when they clearly do not belong there?

Think about it. A movie critic, with little to no exposure to gaming in general, has no basis by which to judge the merits and flaws of BioShock or Killer7 in comparison to Kane and Lynch. By comparison, many gamers who only see a handful of movies may not recognize the reasons why film aficionados praise Citizen Kane or 2001: A Space Odyssey. The two mediums are completely different, and the biggest difference is in the controller held by the player.

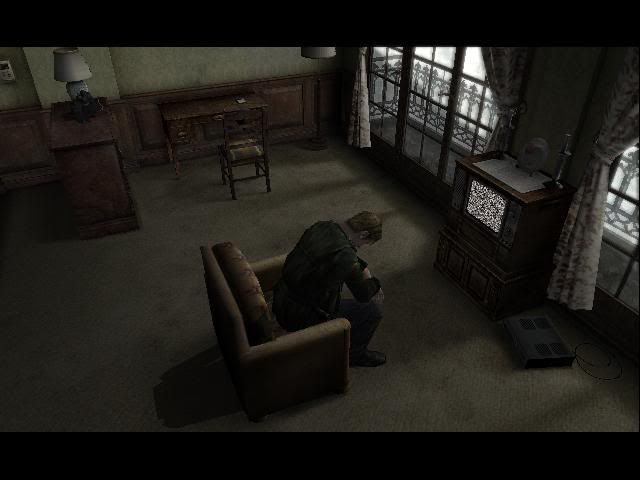

From the moment we put our fingers on buttons, sticks, or mice at the start of a game, we have a measure of control over our experience. A well-designed game lets the player feel like they are truly a part of the world they’re being shown, that their choices will help shape the events to come. In a movie or a book, there’s no interaction between the observer and the observed. We experience the narrative the authors want us to experience regardless of whatever decisions we might have made differently. Video games, on the other hand, invite us to make our choices and experience the consequences for better or for worse.

Since players are a part of the building process for the narrative, it could be argued that they have just as much ownership of the story as the developers do. That isn’t to say they should get a cut of the game’s profits, as not everyone can render the iron sights of a gun or the glowing eyes of a dimensional horror-beast as well as a professional, who has to pay for things like training and food. A game done right, however, makes the player feel like a part of its world, and with that comes a certain feeling of entitlement.

That word’s been bandied about quite a bit lately, and to be honest I don’t think gamer entitlement is entirely a bad thing. The problem arises when gamers act like theirs is the only opinion that matters. Gaming is, at its best, a collaborative storytelling experience. Bad games shoulder players out of their narratives with non-interactive cutscenes or features that ruin immersion. Bad gamers scream their heads off whenever things don’t go exactly the way they expect in a given story. “This sucks and so do you” is not as helpful as “I think this sucks and here’s why.”

Not to belabor the point, but you can tell an author or director how much a book or movie sucks in your opinion, and the most you might get is a “I’m sorry you feel that way.” Game developers, however, know their medium is mutable. It can be changed. And if mistakes are made in the process of creating a game that slipped by them or weren’t obvious, they can go back and fix them. Now, the ending of a narrative is not the same as a major clipping issue, games crashing entirely, or an encounter being unreasonably difficult, and not every complaint from the player base is legitimate. And in some cases, the costs in time and money required to make changes to adjust a story even slightly can be entirely too prohibitive. But when there’s truth found in the midst of an outcry, some merit to be discerned from a cavalcade of bitching and moaning, game developers have power other creators of narrative simply don’t have.

The question is: should they exercise it?

Let me put it another way:

Should finished games be considered immutable things like films or novels, set in stone by their creators? Does listening to players and altering the experience after much debate ruin the artistic merit of a given game?

I think the answer to both questions is “no.”

Changing the ending of a novel or film because fans didn’t like it is one thing. Most directors and authors would cite artistic integrity in keeping their tales as they are. There are those who feel game developers should maintain the same standards. That doesn’t seem right to me, though. For one thing, a writer may change an ending if a test reader can cite issues with it, and a director can re-cut their film if focus groups find it difficult to watch without any benefit. Moreover, gaming is so different from every other art form, so involving of the end user of the content, that sooner or later a different set of standards should be observed.

As we approach the Video Game Singularity, it becomes more and more apparent that the old ways of judging those who create the stories we enjoy no longer apply. We are just as responsible for the stories being told through games as the developers are, and while games empower and encourage us to make decisions to alter the outcome, we must realize that our power in that regard is shared with the developers, and is not exclusively our own. By the same token, the onus of integrity does not solely fall on the developers. We, as participants in the story, must also hold ourselves to a standard, in providing constructive criticism, frank examination, and willingness to adapt or compromise when it comes to the narratives we come to love. Only by doing this can we blur that line between gamers and developers. Only by showing this desire to address these stories as living things in which we have a say and for the benefit of which we will work with their original creators will gamers stop coming across as spoiled brats and start to be considered a vital part of the game creation process.

We can stop being seen as mere end-user consumers, and start participating actively in the perpetuation of this art form. To me, that’s exciting and powerful.

I mean, we still have people using racist and homophobic language in the community, but hey, baby steps.